As 1948 began, Jim Elliot began to spend more and more time studying Greek with Betty Howard. Perhaps this was because she was picking up Greek more readily than he was. Perhaps this was because his interest, kindled during the Christmas visit in New Jersey, was growing.

During that Christmas break, Betty had glumly written in her journal, “Here I am, 21, and no prospect of marriage.”

Like few 21-year-olds, however, she thought in drastically biblical terms. She saw her life as a sacrifice to be put on God’s altar, consumed for His purposes. “My life is on Thy Altar, Lord—for Thee to consume. Set the fire, Father! Bind me with cords of love to the Altar. Hold me there. Let me remember the Cross.”

At the early spring wedding of two close friends, she felt “a calm assurance that I am not to be married. I am grateful to my Lord for winning the victory in that realm.”

In March she clarified, “I do not mean to say that I see the whole plan of my life. God may change it all. I only thank Him for the joy of resting in Him, and trusting Him for every step.”

A few weeks after Betty wrote that, on April 30, 1948, she and Jim actually had a conventional date . . . though of course it was to attend a large Christian conference in downtown Chicago. They were both thrilled by the reports and challenges of a variety of missionaries from around the world. “It was a blessed, encouraging meeting,” Betty wrote. She was moved by two strong, but very different emotions: a deep concern for those who never had a chance to hear the Gospel, and deep respect for her fine companion (as her jumbled journal entry makes clear).

“But O, those 100,000 souls who perished in ‘blackness of darkness forever’ today! What am I doing about it? God give me love! Jim is without exception the finest fellow I have ever met.”

Since Jim and Betty were both prolific writers, their developing feelings for one another—and more important to them, their convictions about God— have been well documented in Elisabeth’s books Shadow of the Almighty and Passion and Purity, as well as their daughter Valerie Shepard’s skillful compilation of her parents’ journals and love letters, Devotedly.

Stunned by Love

Suffice it to say, two very different, yet strikingly similar, souls had come together. Two intense, articulate, unconventional people who saw themselves as perpetually single, serving God on the mission field, found themselves simmering and sleepless, surging with a love they had thought they’d never know. Their individual torrents of prose and poetry brim with the same biblical imagery—altars, crosses, sacrifices for the glory of God. They were strong, stubborn people who shared a radical, intentional submission to Christ. Stunned by love, they were both determined, if God so willed, to sacrifice it for Him.

Certainly other Christian couples they knew were willing to sacrifice anything for Christ, like the other missionaries with whom Jim and Betty would later serve in Ecuador. But few—aside from the 17th century mystics they both loved—articulated their sacrificial mindset with as much detail, passion, intensity, and struggle as did Jim and Betty. We can all be glad they found each other.

“Often we are startled,” Betty wrote, “that our ideas so perfectly coincide—things which neither of us has discussed with anyone before.”

As Jim and Betty began to actually acknowledge their feelings, they did so privately. By the time others found out, some were less than thrilled to find out about the roiling emotions in the “eunuch for Christ.”

Dave Howard—Jim’s best friend, roommate, and, of course, Betty’s younger brother—was at the top of that list. Many decades later, he sputtered to an interviewer: “He went out with her [Betty] every night for two weeks, and he didn’t dare admit it to me. He didn’t dare admit that he, the great celibate, was being attracted to a girl.”¹

It was hypocritical, said Dave—who loved his friend but didn’t want others to put him on a pedestal after his death. “Jim would make all the rest of us feel like second class citizens for even looking at a girl, [or for] dating . . . but. . . that same period of time when he starts falling in love with Betty he is writing some of the steamiest things in his journal about his imaginations.”

Yielded to God

On June 9, 1948, Jim and Betty took a walk, meandering south of Wheaton’s campus. They passed near the spot where Jim had nearly lost his life eight weeks earlier on the train tracks. It was a sweet, early summer evening, teasing of warmth to come. They knew now that they cared deeply for each other. They knew that anything they loved in this life had to be laid on the altar—yielded to God, since His will was supreme.

Fittingly, they wandered through the gateway of a graveyard, most likely St. Michael’s cemetery about a mile and a half walk from campus.

As Betty described it, they sat on a stone slab. “Jim told me that he had committed me to God, much as Abraham had done his son, Isaac. This came almost as a shock—for it was exactly the figure which had been in my mind for several days as I had pondered our relationship. We agree that God was directing. Our lives belonged wholly to Him, and should He choose to accept the ‘sacrifice’ and consume it, we determined not to lay a hand on it to retrieve it on our own.

“We sat in silence. Suddenly we were aware that the moon, which had risen behind us, was casting the shadow of a great stone cross between us.”²

Sometimes such scenes are illumined with meaning only after subsequent events. Not so in this case. Betty wrote in her journal that night, “Tonight we walked up to the cemetery and by chance (?) sat beneath a great cross. How symbolic it seemed! I made known the decision of yesterday. There was great struggle of heart for both. Long spaces of silence – but communion. ‘What is to be done with the ashes?’ It has cut very deep – therefore we dare not touch it. O inexorable Love!”

Jim Elliot set the same scene in his own journal: “Came to an understanding at the Cross with Betty last night. Seemed the Lord made me think of it as laying a sacrifice on the altar. She has put her life there, and I almost felt as if I would lay a hand on it, to retrieve it for myself, but it is not mine—wholly God’s. He paid for it and is worthy to do with it what He will. Take it and burn it for Thy pleasure, Lord, and may Thy fire fall on me as well.”³

They were both perceptive enough to note the shadow of the cross. They just did not know what particular form their crosses would take.

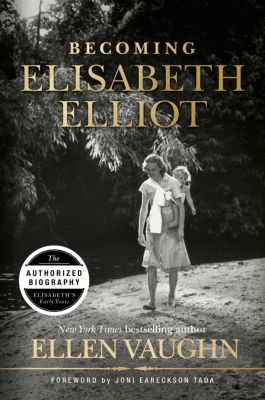

This post was adapted from Becoming Elisabeth Elliot by Ellen Vaughn.

- David Howard, interview with Kathryn Long, May 31, 2000, as well as similar comments in interview with Ellen Vaughn, February 7, 2018

- From Shadow of the Almighty, pages 56 and 57.

- Journals of Jim Elliot, edited by Elisabeth Elliot, entry for June 10, 1948, Revell, Old Tappan, NJ, 1978, p. 65